¶ Systems Thinking

¶ What it is

Systems Thinking is a way of thinking/mindset or an approach to making sense of the world's complexity by looking at things as wholes and relationships. It has been used to explore and develop effective action in complex contexts, enabling systems to change.

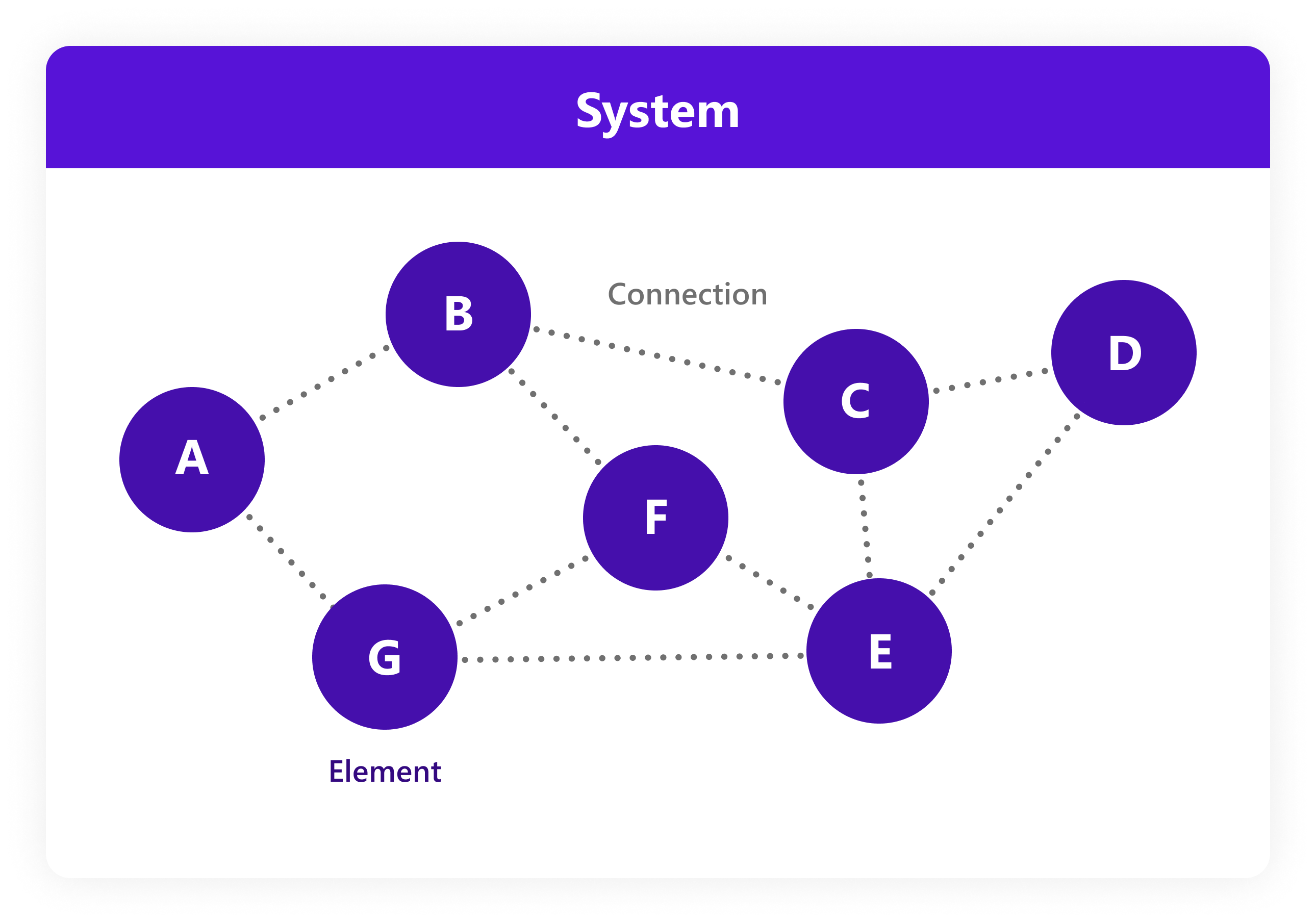

To understand systems thinking, we must first understand what a system is. A system is the interaction or relationship of essential parts that are organised in a way that achieves something. It must have parts that are somehow related to each other, and there must be a purpose or function. So the relationship of elements is integral to a system. And the outcome of all the interconnected parts is the function or purpose of the system.

Furthermore, systems exist within systems. Everything is connected. Systems are everywhere around us. We are part of different systems, whether we realise it or not. That’s why spending time unveiling the various components of the systems you’re part of is crucial.

¶ Six Key Themes in Systems Thinking

Six Key Themes in Systems Thinking

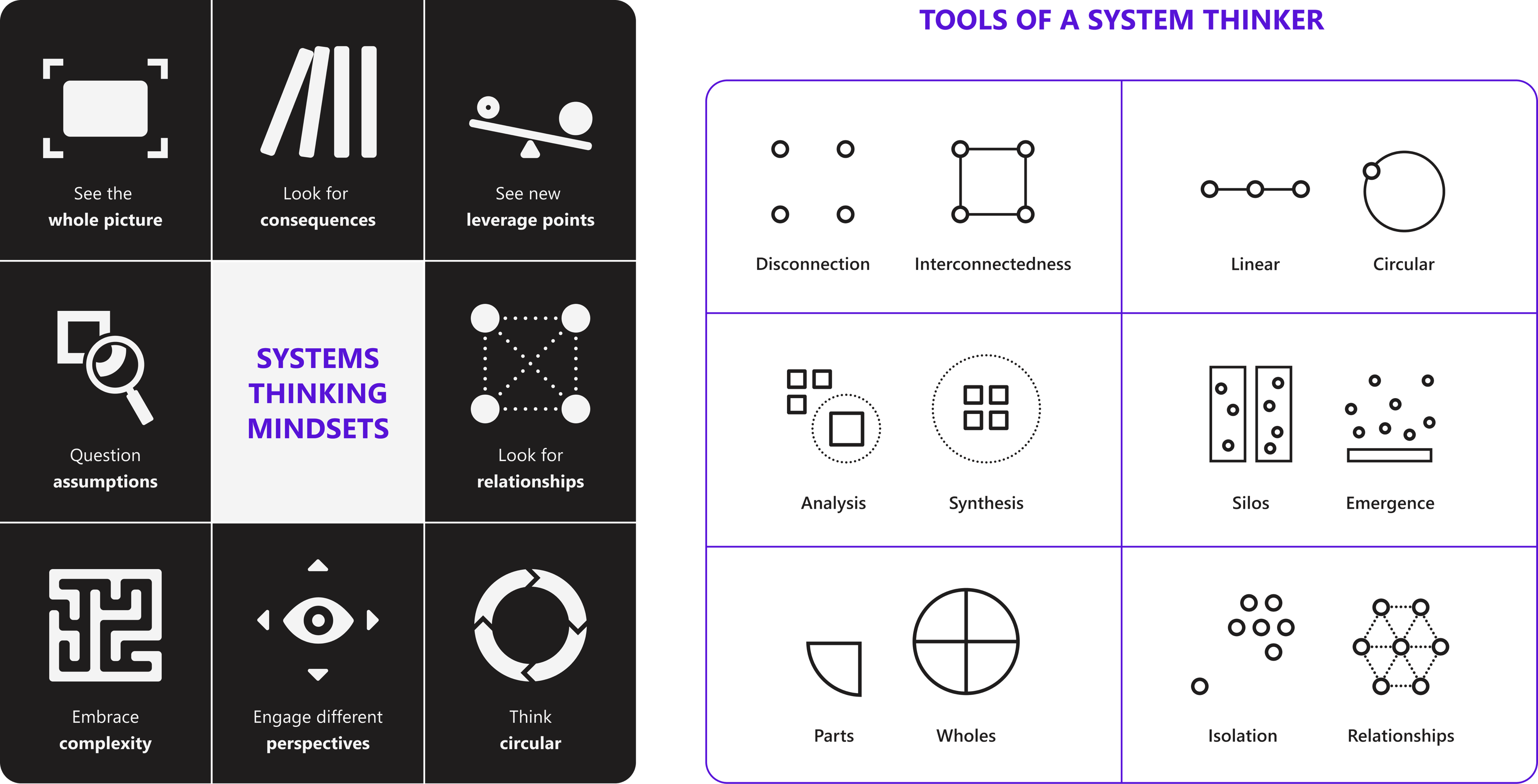

In the mindset of systems thinking, there are six key themes to explore the meanings between different elements in any system. Those themes also indicated the most important applications of this mindset.

1. Interconnectedness

Everything is interconnected as essentially, and everything is reliant upon something else for survival. For example, we need food, air, and water to sustain our bodies, and trees need carbon dioxide and sunlight to thrive. You can always find relationships and connections in anything around you. This is interconnectedness, the way we see the world, from a linear, structured “mechanical worldview’ to a dynamic, chaotic, interconnected array of relationships and feedback loops.

2. Synthesis

In most cases, synthesis means combining things to create something new. But in systems thinking, synthesis means separating complexity into manageable parts to understand the whole and the parts simultaneously. Therefore, synthesis is the ability to see interconnectedness.

3. Emergence

It describes the natural outcome of things interacting with one another. Emergence is the outcome of the synergies of the parts; it is about non-linearity and self-organisation. For example, a snowflake forms out of environmental factors and biological elements; freezing water particles can form beautiful fractal patterns around a single molecule of matter.

4. Feedback Loops

Natural consequences of interconnectedness are the feedback loops that flow between the elements of a system. The two main types of feedback loops are reinforcing and balancing.

- Reinforcing feedback loops involve elements in the loop strengthening more of the same, such as population growth in a big city.

- Balancing loops are comprised of elements in harmony, such as the relative abundance of predators and prey in an ecosystem.

5. Causality

This is to understand how one thing results in another in a dynamic and constantly evolving system and decipher how things influence each other in a system.

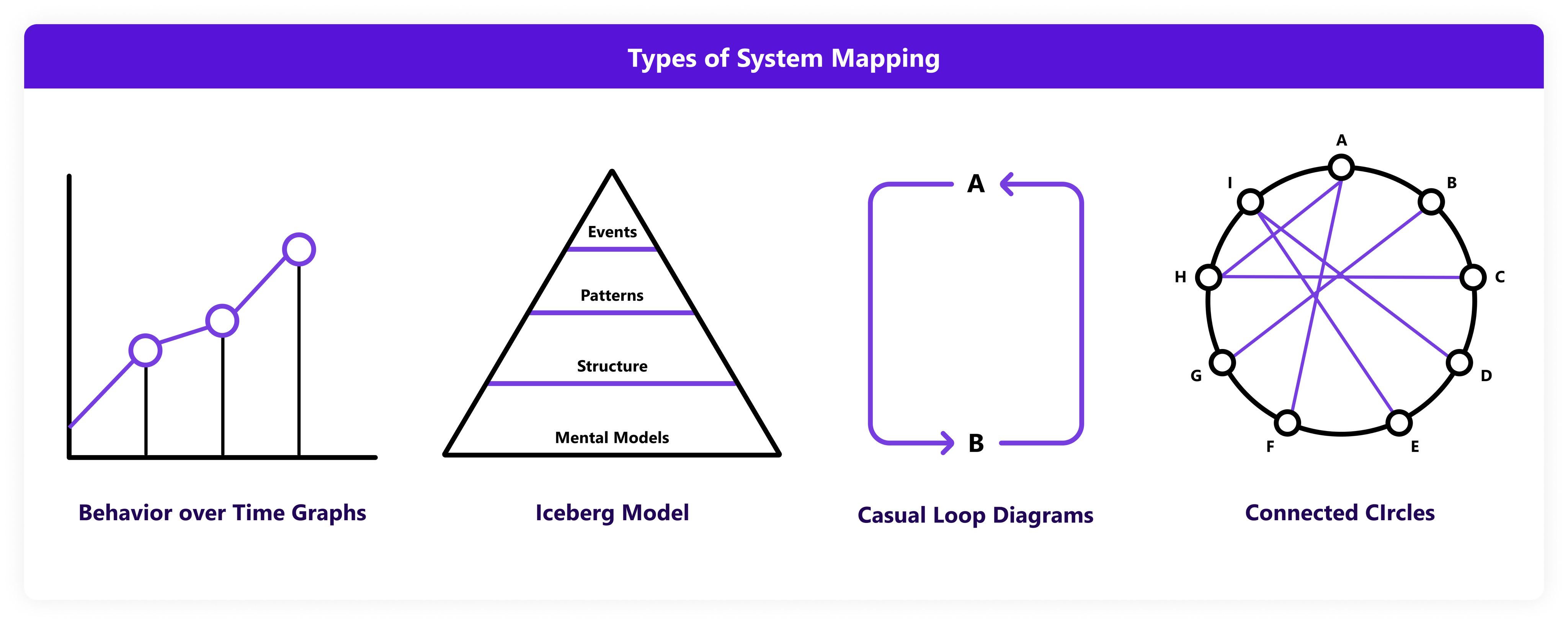

6. System Mapping

Systems mapping is one of the critical tools of the systems thinker. We define how the elements within a system behave and how they are related. Insights can then be used to develop effective shifts, interventions, policies, and project decisions. There are many ways to do system mapping, and we will discuss the iceberg model later in detail.

¶ Why it is useful

Thinking in Systems allows you to see different groups, organisations, and even individuals under the hood. Once we understand what motivates people and drives specific behaviour, we can uncover the main system fuelling their actions. And once we spot these patterns, we can predict behaviours, work better with these people and help them make changes to their current approach so that they can progress faster. Meanwhile, we can also develop better products and services to fulfil their needs.

¶ When to use it

There is no better time to use it, and Systems Thinking is a fundamental thinking mindset we can all apply in our daily work and life. However, we must find some must-apply circumstances:

- The issue is important

- The problem is chronic, not a one-time event

- The problem is familiar and has a known history

- People have unsuccessfully tried to solve the problem before

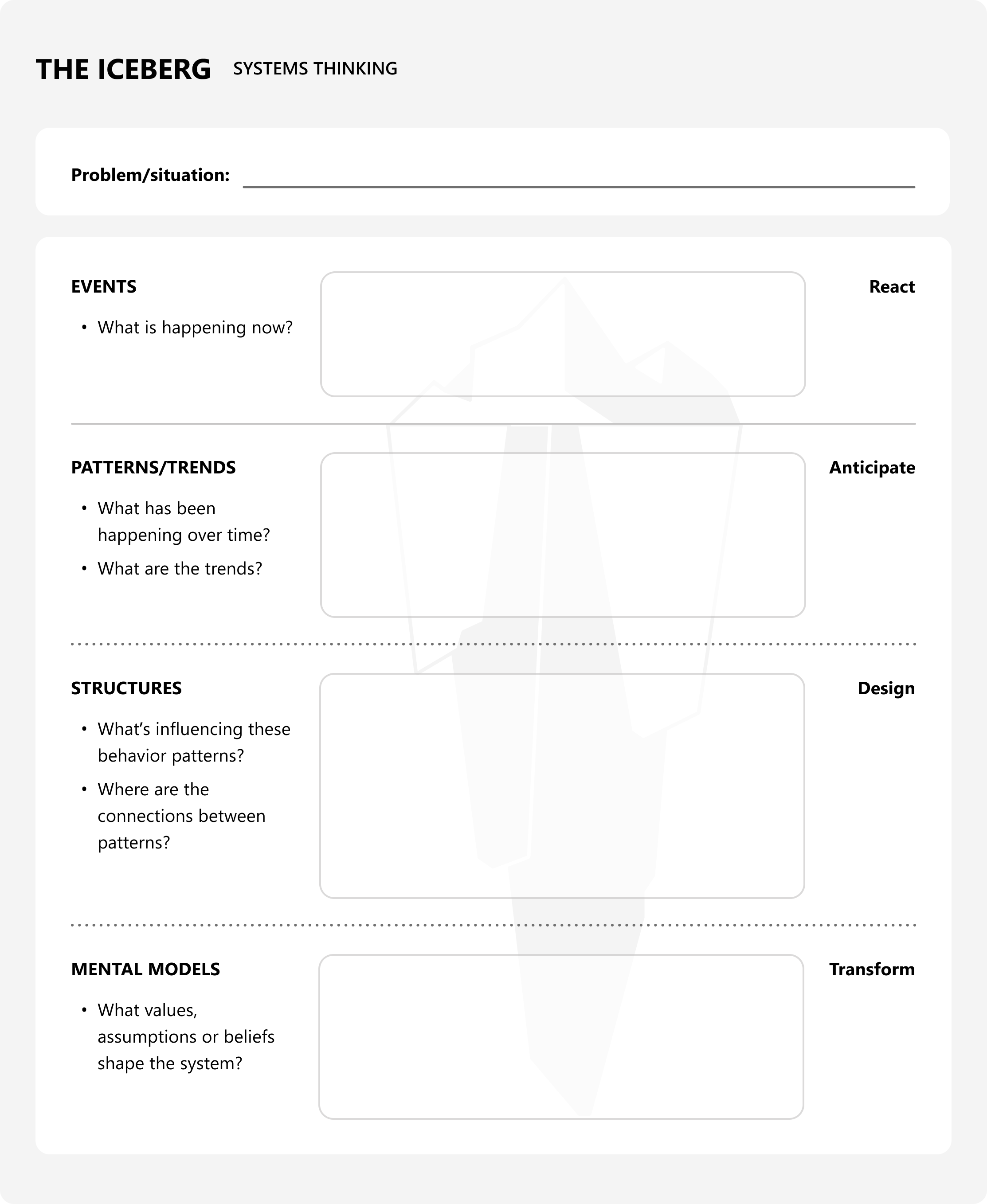

¶ Iceberg Model

¶ What it is

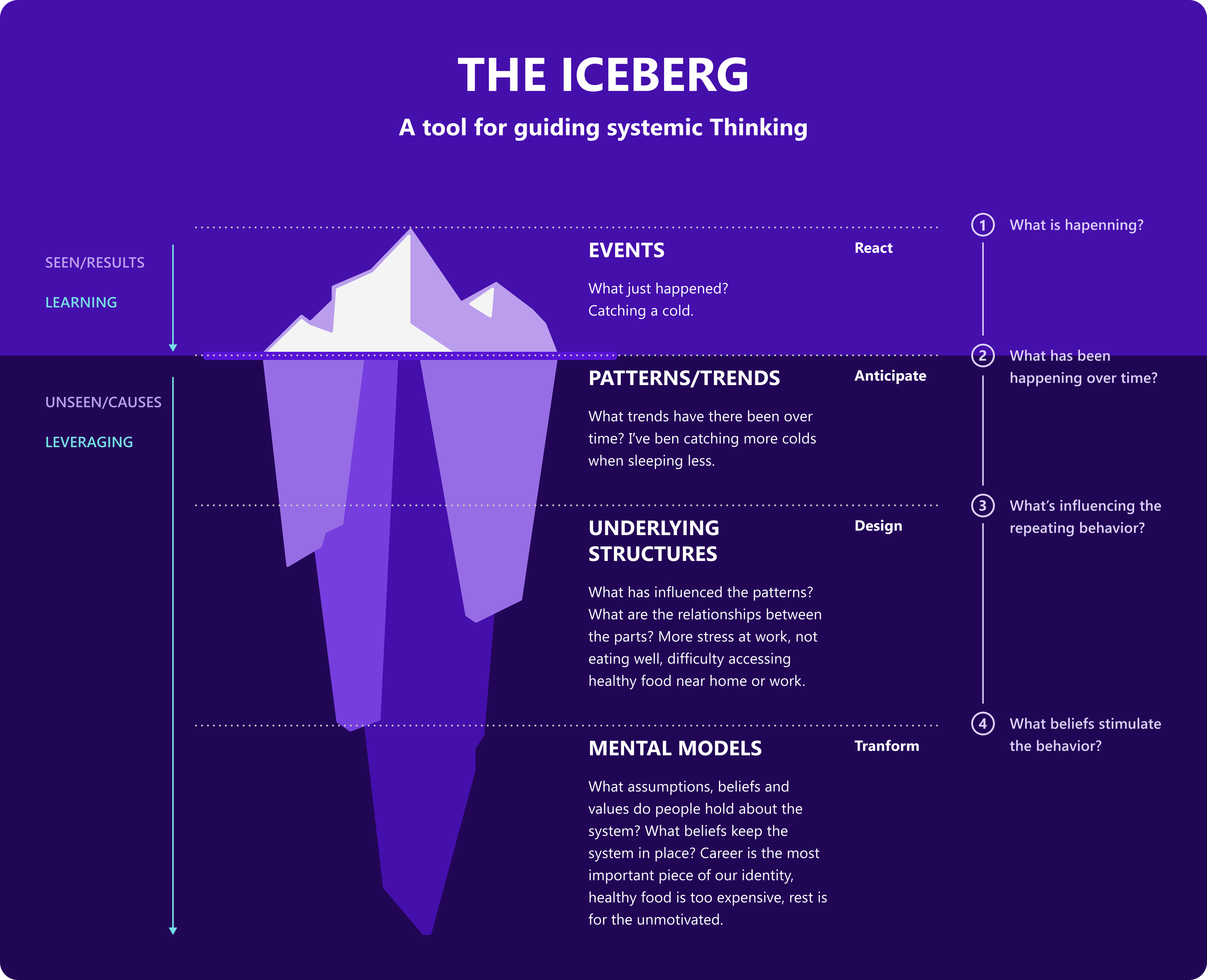

The iceberg model of systems thinking is a way of understanding the origin of a problem. An iceberg is a perfect metaphor for the problems we are experiencing because of what’s visible. But if we react based on a visible event, not going beneath what’s apparent and unravelling the motivations that caused the problem, we might be unable to resolve it. By applying a four-step model, you can reach the core issue and find a better solution.

¶ Why it is useful

It provides an easy-to-follow framework that helps you find the motivations. What caused the behaviour to appear? What chain of thoughts led to a problem? You can uncover the root cause and stop it from occurring. It’s a proactive approach to problem-solving.

¶ When to use it

- When you want to uncover the root causes of a repeated problem

- When you want to re-design a system/product

- When you try to understand how all elements relate to each other

¶ How is it done

Based on this iceberg framework, we will find answers to different questions on each layer and conclude a system feedback loop, explaining how it works and operates.

- Print out or prepare the Iceberg model template (which can be downloaded below the page)

- Identify the source of information and prepare info for analysis

- Conduct relevant research to collect information such as interviews, expert talks, online searches, etc.

- Summarise and synthesise the connections and present your system to the team

- Discuss the next steps and strategy/actions to address this finding.

¶ Tools needed

- Iceberg template

¶ Example

Let's look at a real-world example to better understand how the iceberg model works.

1. First, identify the event: suppose there are a couple of bugs in the feature your product team just released. That's a single event. Your instinct might be to react to it and start fixing them. That's obviously not enough if you want to prevent it from happening in the future.

2. Then you look for patterns: if you look back in time, you see that every released feature comes with several bugs. That's a pattern.

3. Discover current structure: digging deeper, you find that teams don't plan for testing before releasing a feature. The QA only happens after a release. Teams also typically have tight deadlines to ship a feature. These are the structures of the system.

4. Finally, dig out the mental beliefs: investigating further, you discover that teams value shipping on time over the quality of their work. The tight deadlines are imposed by managers, and teams believe it's not their place to push back.

Now after following this iceberg model, you are much more clear on what’s really going on and also the root cause of this problem. It’s a better starting point to choose a solution, whether you want to redesign the project process or reset a new KPI to help the team focus on product quality.